By Cassandra Good, Associate Editor of the Papers of James Monroe

(This content originally appeared as a guest post on The Junto)

The latest volume of The Papers of James Monroe covers a short but important period in Monroe’s life and career: April 1811 to March 1814. Monroe became Secretary of State in April 1811 and was tasked with trying to repair relations with both Great Britain and France. After war with Britain began in June 1812, his focus broadened to military affairs and included a stint as interim Secretary of War. The bulk of the volume, then, is focused on the War of 1812. However, there are a number of other stories revealed here that will be of interest to a range of historians.

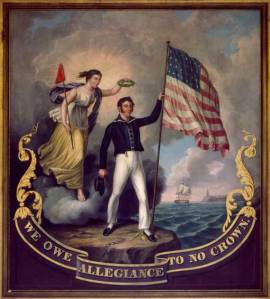

To begin: what new information does the volume reveal about the War of 1812? We know that impressment was a key bone of contention with the British, but these documents suggest it played a bigger role in selling the war than in actually causing it. The correspondence with British ambassador Augustus Foster rarely addresses impressment, and soon after the declaration of war in the summer of 1812, Monroe told Foster’s surrogate that the British restrictions on trade via the Orders in Council were “the only material point of difference between the 2 Countries.”

Monroe’s diplomatic correspondence is supplemented with insights from the writings of his key negotiating partners, the French and British ambassadors. Their official letters home to their nations’ foreign secretaries often record entire conversations with Monroe. Copies of these letters are housed in a collection at the Library of Congress called the Foreign Copying Project.[1] These materials can be difficult to access and use (many are photostats from the 1920s), but they have a wealth of information about American diplomacy. Another helpful source for the volume was Augustus Foster’s diaries, which are brief but often record interesting details. For instance, on the day Foster and Monroe met so that Monroe could officially notify him of the declaration of war, Foster recorded that “Monroe mumbled & shook his Watch Chain.”

Monroe had other foreign contacts with unusual stories. The editor of the renowned Edinburgh Review, Scotsman Francis Jeffrey, traveled to America in the midst of the war to get married and return to Great Britain with his wife, Charlotte Wilkes. He spent two days in Washington talking to Monroe and Madison, recording his conversations at length in his journal (in a nearly inscrutable shorthand).[2] A less upstanding visitor appeared in Washington just before the war, posing as the French nobleman Count Edward de Crillon. Crillon joined forces with the American John Henry to sell the government Henry’s correspondence with the British while Henry had recently served as a spy for them. The men convinced Monroe to spend the State Department’s entire secret service fund of $50,000 on the documents. Crillon was in fact an imposter named Paul Émile Soubiran who was on the run from police across Europe, and the documents had little useful information. Monroe later declared Crillon “an imposter & a scoundrel.”

Monroe did not stay entirely above backroom dealings in this era, however. Like other politicians of this era, Monroe kept close ties with the local Republican newspaper editor, Joseph Gales of the National Intelligencer. He shaped Gales’ coverage in the months leading up to the war and penned a series of seven essays supporting war against Great Britain that were published verbatim as lead editorials in April and May 1812. The drafts of the essays are scattered; one is even in two pieces, with part at the New York Historical Society and part at the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library. At the same time as Monroe was handling diplomatic and later military affairs, he was also regularly fielding dispatches from agents observing or involved in filibustering missions in Texas and East and West Florida. He gave little encouragement to these missions—and sometimes actively discouraged them—in his writings, although it’s unclear what he said in private meetings.

Finally, Monroe was involved in much smaller-scale problems, fielding appeals for his assistance in personal matters relating to the war. Many distressed parents and wives wrote seeking to get impressed sailor relatives freed, including Edwin Bouldin’s self-described “Anxious Mother” Rebecca Bouldin of Baltimore. In other cases, sailors like Ebenezer Allen wrote from aboard British ships pleading for help; Allen declared his “sorrow and grief Being so long from my Whife and famaly.” While many of these sailors’ fates is unknown, Allen later appears in published records of freed sailors. Monroe also received many requests from Americans in the Chesapeake region to board British ships to pursue depredation claims (often for enslaved people who had fled to the British).

Finally, Monroe was involved in much smaller-scale problems, fielding appeals for his assistance in personal matters relating to the war. Many distressed parents and wives wrote seeking to get impressed sailor relatives freed, including Edwin Bouldin’s self-described “Anxious Mother” Rebecca Bouldin of Baltimore. In other cases, sailors like Ebenezer Allen wrote from aboard British ships pleading for help; Allen declared his “sorrow and grief Being so long from my Whife and famaly.” While many of these sailors’ fates is unknown, Allen later appears in published records of freed sailors. Monroe also received many requests from Americans in the Chesapeake region to board British ships to pursue depredation claims (often for enslaved people who had fled to the British).

Very little remains of Monroe’s private correspondence, but a lengthy letter to his niece Emily Monroe in July 1812 provides a detailed glimpse into his relationship with his troubled brother Joseph, Emily’s father. Joseph was perpetually in debt, and Monroe had been supporting him and his family for years, as Monroe explained to Emily in detail. “I always hoped that there would be a period to his folly, and imprudent conduct,” Monroe wrote ruefully, “after which he would apply his talents to useful purposes, establish an honorable & useful character, become industrious, make money, & repay me.” Monroe would send his wayward brother no more money, he declared, but he would support Emily if she needed.

The period covered in this volume was a busy and difficult period in Monroe’s life, which would continue on with the war itself into our next volume. Historians interested in the diplomatic and military history of the War of 1812 will find much new and useful material here. It is the personal stories that emerge from these letters that can be most intriguing, however. From Augustus Foster’s account of Monroe fiddling with his watch as he notified him of the start of war to French nobility to troublesome family members, these letters offer rich vignettes of life in the early American republic.

The Papers of James Monroe are funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the University of Mary Washington.

__________________

[1] The materials are in Foreign Copying Project—Great Britain: Public Record Office and France: Archives des Affaires Etrangères: Correspondance Politique—Etats-Unis. There are guides in the Manuscript Reading Room to navigate the collections, including Griffin, A Guide to Manuscripts Relating to American History in British Depositories; Paulin, Guide to archives for History of U.S. Since 1783; État numérique des fonds de la correspondance politique de l’origine à 1871; and finding aids on file in the reading room.

[2] A complete publication of Jeffrey’s journal of his travels is published in Claire Elliott and Andrew Hook, Francis Jeffrey’s American Journal: New York to Washington 1813 (Glasgow: Humming Earth, 2011). The transcriptions in this volume are somewhat problematic.

Speak Your Mind